|

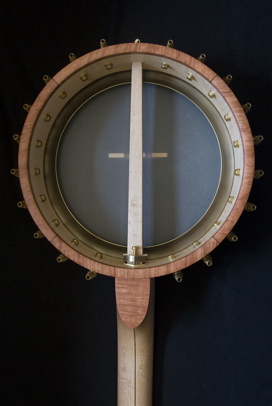

| Front view. |

|

|

| The peghead and fingerboard. |

|

|

| Heel cap and rim cap woods. |

|

|

| Rickard Dobson tone ring. |

|

|

| The "S" scoop, EVO frets, and abalone position markers. |

|

|

| Peghead showing the rake angle. |

|

Banjo building has become a passion in my life. For as long as I can remember, long before I played music, I have loved musical instruments and have wanted to design and craft my own. Lutherie combines graphic design, sculpture, and construction in a way that has caught my imagination like no other art form. It also calls me to do things with my hands and simple tools to a degree of accuracy and perfection that still seems a bit beyond my seemingly less than perfect natural abilities. When I see the finished product take shape beneath my touch in front of my disbelieving eyes, it reminds me that the world is truly magical.

The banjo shown on this page has an 11" pot and a 26 3/16" scale. The inspiration for the peghead shape came mostly from a page I once saw showing a variety of peghead profiles. Though there seem to be no current or historic peghead profiles that exactly match it, it is somewhat reminiscent of the old Gibson shape, with a bit more pronounced curves, different proportions, and a sharper point at the very tip.

I feel a deep love for wood grains and natural colors, which is reflected in this banjo. The pot is constructed using curly maple heat-bent into a two-ply hoop. For the neck, I hand selected a massive piece of maple lumber from a local hardwood supplier. I frequently visit their stacks, picking through and selecting pieces that are best for neck carving. I like them to have basically straight grain to assure that they won't be prone to warping and the grain must slice through the endgrain at a particular angle that makes for a stronger heel. After those criteria are met, I look for the pieces that also have the best decorative characteristics. I was able to find a piece that had nicely straight grain at the proper angle, yet also has some attractive curl and birdseye. I was able to make four neck blanks from that one piece of lumber.

To make sure that the neck will always remain stable, I start each neck blank with a piece 1.5″ thick and 60″ long. After planing it square on all four sides, I cut it in half and oppose the grain in a technique that is similar to book-ending techniques common in arts and crafts era furniture. Viewed from the end, the grain pattern of the two sides of the blank mirror each other. That way, should the natural grain have any subtle tendency to warp one way or another, the opposite grain in the adjoining half will counteract it. To create an attractive visual line, I include a thick walnut veneer between the two halves. The resulting 3″ x 3″x 30″ blank is extremely stable so a neck constructed from it will always be straight and true. Nevertheless, I include a two-way adjustable truss rod, for the unlikely chance that minor adjustments to the neck bow need to be made. To preserve the simple lines, I hid the access to the truss rod adjustment nut in the end of the neck where it adjoins the pot so no truss rod cover mars the look of the peghead.

It is also important to point out that once the neck blank is made, the entire neck, including the peghead and heel, is all carved out of a single blank. This technique yields instruments that are stronger and more attractive that those made by other techniques. When designing instruments for mass production, factories necessarily make compromises so that instruments can be made less expensively and on high-speed automated equipment. Those changes may includeshaping the peghead, heel, and main part of the neck as two or more separate pieces that are splined together to make the finished product. I feel that results in a weaker finished product and also takes away from the clean, sculptural lines of a one-piece neck.

Complimenting the warm amber color of the maple is red-orange madrone burl, from which I milled the fingerboard and capped the peghead, pot base, and heel. The rim cap is divided into four quadrants, with a thin strip of walnut in between each. The entire rim cap and heel cap are also underlain with walnut, making a continuous walnut line around the pot and the heel.

Also reflected in this design are my environmental ethics. It is sad that the world's exotic hardwood forests are disappearing and with the raid last year on Gibson's factory, the use of exotic hardwoods can have significant legal implications as well. Though the banjo's roots are in Africa, it has certainly found a home in North America, so it is completely appropriate and ecologically responsible to use our unique and beautiful North American hardwoods to make banjos. The maple in this banjo is from the eastern woodlands, the walnut is from the south, and the madrone is from the northwest coast in Oregon.

From even farther north is the special hardware used on this banjo. All of the pot hardware is made by Bill Rickard in Canada. Bill makes some of the most beautiful, functional, and strongest hardware I have seen. The hardware on this banjo is raw brass, meaning that it is not coated with anything to prevent it from aging gracefully and acquiring an amber-gold patina. The color compliments the woods perfectly, giving it a rich look that will improve over time. The tone ring is Bill's reconstruction of the design patented by Dobson in the late 19th century. I added a 1/2" integral tone ring of claro walnut that mates with the Dobson tone ring in a precision press-fit. The Dobson ring gives the banjo good clarity, ring, and sustain and the claro walnut helps it retain a rich woody tone. The best of both worlds.

The tuning machines are planetary-geared Gotoh double band. In my experience, they are the smoothest, best -feeling tuners around. The peghead is cut to a steeper angle than most banjos which improves the sustain characteristics of the instrument's tone and certainly looks cool. The main nut and the fifth string nut are both bone, and the fifth string nut is hand turned from a bone knitting needle. Bone was considered by many prehistoric Native American people to be a valuable high-tech material from which they made weapons, tools, and personal prestige items such as jewelry and hair pins. To this day it is still the finest material available for musical instrument nuts and bridges, unmatched in tonal qualities and durability.

You may have noticed that the frets have a look and finish that virtually matches the raw brass. They are made from an alloy that is relatively new to fretmaking called EVO. It is a copper alloy that has been used for years in the optical industry. Its hardness is between nickle silver and stainless steel and the frets are gold all the way through so the gold color will never wear off.

The fretboard is scooped in an "S" shape and the position markers are inlaid abalone dots. The side position markers are even inlaid with abalone dots that are just 3/32" in diameter.

Specifications:

Scale: 26.188"

Neck width at nut: 1.375"

Pot Size: 11" diameter, 0.5" wall thickness, 3.125" deep

Rickard Dobson-style spun brass tone ring

Curly maple pot with madrone burl rim cap

Bookmatched laminated maple neck with light curl and birdseye

Madrone burl peghead overlay

Pressure stabilized madrone fingerboard

"S" shaped frailing scoop

Gold toned EVO alloy fretwire

Paua abalone inlaid position marker dots at frets 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, and 15 (two dots at the 12th fret)

Matching Paua abalone side dots

Twenty hooks

Rickard raw brass hardware

Gotoh two band planetary tuners

Custom made 0.75" bridge from cocobolo and maple

Bone nut and hand turned bone 5th string nut

No knot tailpiece

Remo Renaissance head

Ships with padded gig bag case

Price: $2390.00 SOLD

|